Probably, as far as intersections go, the epicenter of

Philadelphia, at least from a Cheesesteak perspective, is the funky intersection

of 9th Street and Passyunk Avenue in South Philly, where you can find both

Geno's Stakes and Pat's King of Steaks.

However, for me, my favorite corner was a much more interesting

place. It was on the line between

Darby, PA and Philadelphia. Both

streets changed names. Island

Avenue/Island Road change to become the Cobbs Creek Parkway. Main Street from Darby becomes Woodland

Avenue in Philadelphia. Main

Street/Woodland Ave. carried the #11 Trolley from Darby to Center City (and

still does).

Lets start at the Trolley station in Darby, and catch the

#11.

The cobblestones on Main

Street, while tough on the ankles, would have lasted as long as cockroaches and

twinkies after the world ends, were it not for the brilliant whoever who

decided to remove them decades ago.

This trip is full of decisions. Which side do

you want to sit on? What window do

you want to look out of? If

you sit on one side of the trolley, you can look at the houses and stores of

Darby drift by. If you sit on the

other side, once you get to 4th Street, you get to look at the homes of Colwyn

until you get to my favorite intersection. 4th Street, 3rd Street, 2nd Street, Front Street, and

finally Water Street pass by on the Colwyn side. The houses are all up on hills, above Main Street.

On one side of Front and Main in Colwyn

is 20 Main Street, where my grandparents lived for years, and where I spent

much of my summers when I was young.

It was a good life - I had a group of kids on my street in Collingdale

who I played with, and when my mother went to her parents, which she often did

in the summer, I had another set of kids there to play with. The kids in Collingdale were

"good" compared to the kids in Colwyn. I enjoyed both, but the Colwyn kids enjoyed exploring much

more - "getting into things" as my mother would say. Plus they always seemed to have

firecrackers, and knew where to find "punks". Real ones. A few blocks away there were some garages, and a big wooden

fence with a loose board that would let us get into a part of the train yard of

Fels (more on this later). There

were four train tracks (that seemed like twelve) that passed through this

forbidden spot. Fast trains -

Amtrak, as well as freight trains, I seem to recall. Crossing the tracks really was extremely dangerous. You couldn't dodge an express at full

speed. It probably wasn't wise to

put our ears to the track to hear if a train was coming either. We used to put pennies on the track, to

let the train smoosh them to the size of silver dollars (so the lure went) but

we never did find a penny after it was run over. Of course, there was also the fear that, as lure also went,

you could derail a train this way.

On the other side of the tracks was, as always, a

"woods". For some

reason, every town seems to have unfinished areas that are left as woods. This woods, which you can get to if you

survive jumping the tracks, had the Cobbs Creek run through it, and a little

pond I seem to recall. If you look

at a map, you'll see that you could walk in the woods and end up all the way

out by I-95 at the Tinicum Wildlife Preserve! I remember going to this woods with my Colwyn friends for

the first time. It must have been

like how it felt for the founder of the Mormons when they came out of the

mountains and saw the valley below, now Salt Lake City, and said, "this is

the place". When I first saw

the middle of the woods, with groups of kids playing there . . . I had no

idea! A little kids Mecca - and

I'm sure few of their parents had any idea where they were. Our own little lost world.

Back onto the trolley.

After we pass Front Street and Water Street, on the Colwyn side you ride

on a bridge, over the Cobbs Creek, and can see the grounds for the Fels Naptha

Soap Company, also called Fells & Co.

The factory, which made Fels Naptha Soap, was built on a source of

water, as factories often were, and was on the train line as well.

It was a pretty well protected property

- not the kind of place you could walk onto, unless you knew where the one

loose fence board was. Of course,

I could get into the factory whenever I wanted - I would even get the grand

tour and be introduced to everyone.

My father worked there.

Often he would walk to my grandparent's house for lunch, or my mother

and I would take lunch there for him, or I would walk there by myself and he

would take me to the Fels cafeteria for lunch.

I don't want to get too far away from the Colwyn corner of

Front and Main. As I said my

grandparents lived on one corner.

On the other corner was a house on top of a much higher hill, with

dozens of steps from Main Street up to the front porch. Along The Front Street edge of the

property there were several garages, built into the side of the hill,

presumably built because the other houses had no garages, and these were rented

out - not to anybody we knew, but the garages were always full.

"The Old Man" lived alone in this house for years,

and then he died and it went up for sale.

While we never were up close to the house, lest we get caught and eaten,

we did find the garages interesting, and the cars in them that never seemed to

move, and didn't appear to have owners.

Each garage door had upper windows, which we could see in if we stood on

our tippy toes, which we often did, so we knew. We knew that one garage, and only one, had a door on its

back wall. It could only be one

thing, it had to be a door that lead to a stairway or passageway that went up -

up to the house.

Shortly after the Old Man died, the car owners must have

been contacted, because one day the garages were empty and unlocked. Within a week, they were all padlocked closed,

but we took advantage as soon as we could. My Colwyn friends and I slipped, one by one, through the

barely open garage door and into the dark, clammy garage. We stood in front of the solid wood

door on the back wall, and one of us finally got up the nerve to touch the doorknob. The door was unlocked, and up we went,

up a staircase, in total darkness, almost on hands and knees, feeling the next

step, then the next, not even talking, not knowing who may be in the

house. The first of us finally bumped

their head on soft wood, the top of the staircase. We sat there and listened, and hearing nothing, again tried

a doorknob, and the door opened into a well-lit room on the main floor, bright

sunlight shining in, no curtains or shades anywhere. Again we listened, again, it seemed like we were actually

alone. The house was three stories

high, a tall house on top of a big hill.

There was little wallpaper on the walls. There was no furniture. It was almost as if someone prepared the walls to wallpaper or

paint a decade earlier, and never did it.

Many of the rooms had fireplaces.

It must have been an incredible house in its time. There were two staircases that went

from the first floor to the second.

Drawn on the walls, some of them, were arrows - arrows drawn in

pencil. They were hard not to

follow. They pointed up the steps

to the second floor. Some of us

followed one set, some followed the second set. Both led upstairs.

Both sets of arrows led to the same wall, in the same room, on the

second floor.

Back on the first floor, on the shelf above the dining room

fireplace, sat a beautiful old camera.

It must have been made of mahogany with a black bellows. It was a large, professional

camera. Its color, against the

stark off-white walls, was striking.

It was also scary. Someone

swore they heard a creak upstairs.

We realized that we had no game plan. What if someone came up the steps from the garage? Which way would we go? What if we were on the third floor and

the front door opened? Would we

hide? Run? The exploration was over. We found a light switch that lit a

series of light bulbs all the way back down the staircase to the garage, and

another switch that let us turn them off at the bottom. We slipped out one at a time, leaving

space between us in case parents saw us, but no one did. At least no one that we know of. Urban exploration like this has always

been one of the most exciting things to do, I've found.

If we continue on the trolley ride to my intersection, you

now know that the Fels & Co. factory takes up one corner. Across the street, if you had been

looking out the other side of the trolley we were riding on, you'd see a falls

on the Cobb's Creek, and on the corner, a little house.

The sign indicates that it is a

historical site, the Blue Bell Inn, where supposedly George Washington actually

slept! At this point, Main Street

becomes Woodland Avenue, so as you go through the light, you move from

Darby/Colwyn into Philadelphia.

On the corner adjacent to the Blue Bell Inn is a little

triangular "block" that I think just had a little parklet on it. Whenever you have five square feet or

more of grass, it's officially Fairmount Park in Philadelphia. I'm not even sure if there was a bench

there, but there had to be.

There is the fourth corner, which was really an exciting

place for me to go with my father on a Saturday morning. On the corner, I forget, but I think it

was a Pep Boys store. I loved the

smell of the place. They sold car

parts, bicycles, all kinds of great guy stuff. There was a narrow alley that led to a garage behind the

store, where you could get work done on your car. Adjacent to the alley was another alley that went back to a

garage behind the next store, which was a Penn-Jersey Auto Parts Store! Pep Boys and Penn-Jersey were

independent but very, very similar stores. Being able to cruise one, then go next door and cruise the

other, was great fun. It made

about as much sense as having gas stations on adjacent corners. I mean, what kind of sense could that

possibly make, right?

Behind Pep Boys and Penn-Jersey was another building, off of

Island Rd., which held white collar offices and the cafeteria for Fels

employees.

Fels owners and workers

ate together there. Workers went

because it was very inexpensive, and owners because it was such a good deal

they couldn't pass it up either.

There's a lot of history on this corner, although its almost

all gone now. If you're

interested, read on. If not,

thanks for reading this far! If

you stay on the trolley, heading into town, you'll pass some great places that

aren't around any more, like the Breyer's Ice Cream factory. (William A. Breyer sold "a

relatively new concoction called ice cream" in 1866, first from his home

in Philadelphia, and later on the streets using a horse and wagon. The company was eventually sold and for

awhile owned by Kraft. Now

Breyer's is owned by Unilever, since 1993.)

Lets get back to the Blue Bell Inn in Colwyn.

There is a short video on YouTube so

you'll know it actually exists.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QHPcfPmoSfE

It

is a "George Washington Slept Here" kind of place.

Built in 1766 by Henry Paschall, it was

a stagecoach stop for coaches heading south out of Philadelphia.

It is also the site of Pennsylvania's

first water-powered mill, sometimes called Printz's Mill or Old Swedes Mill,

built around 1645.

I'm assuming

the Mill site is somehow related to the falls that are on the Cobbs Creek, just

a few yards away.

This is not to

be confused with The Blue Bell Inn in Blue Bell, PA (open since 1743).

I had mentioned the adjacent corner, a small triangular

"block" that was just a "park", surely a part of

Philadelphia's system of parks, Fairmount Park. Cobbs Creek is surrounded by Cobbs Creek Park, which is a

major part of the Fairmount Park system (the largest urban park in the

country). According to Wikipedia,

"For many West Philadelphia and Upper Darby children, Cobbs Creek is their

first introduction to wooded greenspaces and freshwater ecosystems. . . . The

wildlife includes regional birds, raccoons, opossums, spotted deer, wild

turkey, rabbits, and in recent history, even a mountain lion."

Across from the park triangle, in Philadelphia, is the

corner where Pep Boys and Penn-Jersey coexisted for many years. (I can still smell the inner

tubes!) According to their

website, four Navy buddies, "Mannie" Rosenfeld, "Moe"

Strauss, Moe Radavitz and "Jack" Jackson, all from Philadelphia, put

together $800 (in 1921) to start an auto parts supply company. The Manny, Moe and Jack characters were

modeled after the founders. One of the Moes, Moe Radavitz, left after only a

few years.

They started out as Pep Auto Supplies, and the story tells

of a Philadelphia policeman who worked near their first store, who would often

send people to go see the "boys" at Pep, so the "Pep Boys"

was in common usage before they changed their name. They chose the official name of "The Pep Boys-Manny,

Moe & Jack" because Moe noticed that lots of businesses used first

names, such as a local dress shop called "Minnie, Maude and Mabel's". There are currently over 700 stores

across the US (Pep Boys, not Minnie's).

One of the original Pep Boys, "Moe" Strauss, had a

brother, Izzie Strauss. He started

Strauss Auto in Brooklyn, which later became Strauss Discount Auto. In 1987, the company acquired

Penn-Jersey Auto Parts. Small

world.

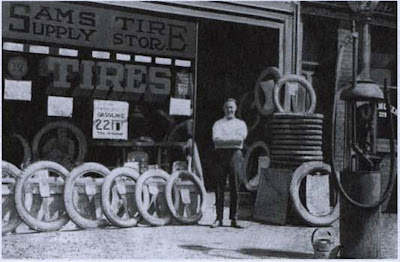

The Penn-Jersey Auto Stores were founded by Samuel H.

Popkin.

His first store, in Easton

PA in 1920 was called Sam's Tire Supply Store (according to the Philadelphia

Jewish Business Archives).

Most of

these stores and factories were created by Philadelphia's Jewish community

leaders.

They built much of modern

Philadelphia.

On the remaining corner is the Fels Naptha Soap company

factory, which I'd like to say a little more about. Fels Naptha soap is a harsh soap known for handling heavy

grease and oils. It was Joseph

Fells who developed a new soap-making process in 1895. It started as a home remedy for contact

dermatitis, such as exposure to poison ivy - "oil-transmitted

skin-irritants." It became a

laundry room standard - reliable and cheap. The product was so successful, Fels built a factory in

Southwest Philadelphia, a "water-powered mill-seat on Cobbs Creek." At it's peak in the 1930's, the factory

employed more than 600 employees.

It is now essentially demolished and a gas station has been built on

that corner.

One reason why Fels Naptha soap became so popular was the

efforts of Anty Drudge.

According

to "Adapting to Abundance: Jewish Immigrants, Mass Consumption, and the

Search for American Identity." by Andrew R. Heinze (1990, Columbia

University Press), Aunty Drudge advertisements were considered as Yiddish

advertisements.

In many

newspapers, there was often an Aunty Drudge column, in which the Aunty Drudge

character gave housekeeping tips, which often discussed a problem where Fels

Naptha soap was the solution.

Heinze writes:

"The

value of being up-to-date, as well as time-conscious, was reinforced by Yiddish

advertisements.

Fels Naptha soap,

the well-known brand of a Jewish soap manufacturer, was regularly advertised

with the character of "Aunty Drudge," a matron who instructed readers

in the progressive approach to cleaning.

At times, a drawing of an attractive, fashionably dressed young woman

helped to convey the message that Fels Naptha would help keep a woman

up-to-date."

Whenever Aunty Drudge (anti-drudge, get it?) was drawn, her

dress resembled a bunch of Fels Naptha Soap wrappers sewed together. She is sometimes referred to as Anty

Drudge.

I do have a small book, "Anty Drudge's Cookbook"

(A Cook Book of Tested Recipes, Containing Many Helpful Hints for Housekeepers,

Compiled by Anty Drudge, Who will gladly answer any questions or give advice

about housework and cooking), from Fels Naptha, Philadelphia, 1910.

There is a different "verse"

at the top of each page. For example, "Fels Naptha soap makes clean

clothes - fresh paint, spotless homes, rested women - happy families."

The recipes, sometimes for complete

meals, always are inexpensive, sensitive to the needs of the woman of the

house, easy to prepare, easy to clean up, etc.

Several recipes come under the "fireless cooking"

category, and there is a large section on paper bag cookery, in which food,

sometimes meals, are cooked inside a paper bag in the oven (and some people

thought it was just a fad!).

So that's my story of my favorite corner.

Everyone should have one, don't you

think?

It was pure Philly.